You may think you know Diane Keaton. Annie Hall. The Godfather trilogy. Something’s Gotta Give. The hats and the “I do things my own way” fashions. But there’s so much more to the Academy Award-winning actress. Keaton is a single mom of two adopted children. She’s a board member of the Los Angeles Conservancy and actively campaigns to save and restore historic buildings. She’s a real estate developer. She’s a photographer. And she’s also someone who has been affected by Alzheimer’s.

You may think you know Diane Keaton. Annie Hall. The Godfather trilogy. Something’s Gotta Give. The hats and the “I do things my own way” fashions. But there’s so much more to the Academy Award-winning actress. Keaton is a single mom of two adopted children. She’s a board member of the Los Angeles Conservancy and actively campaigns to save and restore historic buildings. She’s a real estate developer. She’s a photographer. And she’s also someone who has been affected by Alzheimer’s.

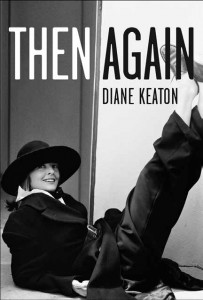

In her new memoir, Then Again, Keaton intertwines her own writings with the personal journals of her mother, Dorothy Keaton Hall, who lost her 15-year battle with Alzheimer’s in 2008.

Preserving Your Memory magazine spoke with Keaton about her career, motherhood, the devastating effects Alzheimer’s had on her family, and how her mother’s detailed thoughts and struggles led to Then Again.

PYM: Your mom started a memoir called Memories. Is Then Again your way of paying tribute to your mom by not only continuing her memoir, but also merging your own?

DK: The answer is yes. That’s true. I think when I came across that, I was reading everything out of order. As I’d go, I’d pick one year, and then I’d write about that year, my response to her and what she was writing about. And then I came across this one year, she must have been in her 50s, and I remember just how sad it was. Because she was

really talking about her girlhood days, and about the things that she loved about it but also about the losses, about her father and how he took off when she was 16, and she was his favorite. And I remember thinking, oh my God, I never even helped her. She mentioned she was writing this autobiography on her own, but she never completed it, of course, because there was no real outlet for her. And I didn’t help her, which I could’ve at that point, of course, because I was established. So it made me really quite sad. It was a letter I didn’t really pay any attention to what she was talking about. I mean, she didn’t have any excerpts in there or anything, she would just mention that she was doing this. And I just put it aside, like so many other things I should’ve paid attention to. But I didn’t.

You said your mom has been the most important influential person in your life. And yet the two of you seem very different. Do you think those differences are what made your bond so strong?

When I came across that, I thought there’s so much that’s so similar. I think the differences were really based on time and place and circumstances. When you were born in the ’20s versus being born in 1946. Very different times. More opportunities. My mother’s experiences, and what she gave to me from what she learned from her experiences and her

dreams that she never really spoke of, obviously loomed very large. The choices she made when she was a young wife, putting us on TV shows in Burbank. I don’t know whether I mentioned this in the book, but my brother Randy and I appeared on Art Linkletter’s Birthday Party, and we were just sitting there with a bunch of other kids, who it happened to be their birthday. We never made Kids Say the Darnedest Things, which was too bad. Mom was obviously very interested in entertainment, and in her early days she took piano lessons from Gloria Grahame’s mother, so can you imagine, she’d go over to Pasadena. Gloria Grahame’s mother lived in one of those California bungalow-type houses. I think my Mom had a lot of fantasies about performing. She was a singer in Three Dots and a Dash, which was her high school singing group. It’s just really similar in a lot of ways, that I just latched onto entertainment immediately. I was the only one in our family who was so determined. And the determination was instilled early on by the fact that I inherited some of my father’s genes, as well, and he was a very determined fellow with regard to his occupation. I have my mother’s sensitivities and insecurities. I also have her longing to be part of an art world, part of art in general. She loved art. She was constantly a craftsperson—I also mentioned that in the book—shell boards and rock boards and mosaics. She did that thing that everyone did in the ’50s—she made a mosaic table. She never stopped. Everything you could possibly do, my mother did—sew, cook, every bit of it. Of course I was more fortunate because she was my mother, and it was a different time.

Was seeing her on stage what first sparked your interest in acting?

Oh, yes. Before that I had fantasies, of course. We went to the First Methodist Church every Sunday, and I was in the choir. I did everything, and I wanted to. But I think it was solidified in my mind from the image of a curtain opening—this huge red velvet curtain—opening to my mother on stage, next to a lot of large appliances, and a crown on her head. So you see, I kind of got it. It was deeply implanted, forever and ever.

I know in the book you mentioned that you stopped reading her journal, and then you came back to it after she passed away.

The way it went was, I’d be around. We’d always come down to my Mom’s house, all of us, my sisters and brother, every holiday was with Mom after Dad passed as well. I’d say it was in the early ’80s, I would go down and visit my Mom and Dad, and there were these journals around. And I would occasionally see them because they were never hidden. And they were also combined with collage elements, there were pages of collage in them, as well, they were kind of a massmedia production. And I came across a passage that was too embarrassing, and I closed it, I couldn’t read it. I didn’t want to read it. I didn’t want to know aspects of my mother’s life that were painful or that reminded me of something I instinctively knew was going on, but I couldn’t address because I wasn’t ready for it. So, really I didn’t start reading my mother’s journals until I made the decision to write the book, and when I made that decision I knew it would be a co-authorship. There was no way it wasn’t. She had so much material, and I had to delve into it. It was very revealing, and it was a very emotional experience for me to get to know my mother in a way that I avoided. It was a wonderful opportunity for me that I wouldn’t have taken.

It is beautiful that you are so accomplished, and you’ve written this great book in which you can share ideas and feelings that are personal with many people who have gone through something similar.

That’s because I’m an actress! Or I wouldn’t even say an actress, I would say, that’s because I am a performer. Whatever I do. I feel everything, and I’ve got to express it. That’s what I do. My mother was that way, too, except she kept it more hidden because it really wasn’t accepted back then, I think, when she was a girl, growing up under this kind of umbrella of Christianity telling her she couldn’t wear lipstick and couldn’t dance, all those restrictive rules that applied for her at that time, with her mother being a devout Christian. It just wasn’t the way it was for me. If I was acting silly, they would laugh—they didn’t care. They never said, “That’s not what a girl does.” My mother never told me that I had to get married, or you’ve got to find the right man and settle down and have a family. She never preached to me about what I’m supposed to do with my life. And when I was in my 20s and 30s, I thought, “You should’ve told me!” But basically I really don’t believe that any more. I’m glad she gave me my independence and gave me the ability to find out for myself what I felt and what I thought. She was a modern mother, even for that time. She was more avant garde, more willing to try things that were unusual, to take you to the art museum to see what was going on.

I’m sure it was devastating to go through the 13 years of her decline, and the effect it had on your family. One of the great things about the book is that you do share with your readers what the entire family was going through. Was that something that was important to you, to show how a family deals with the effects of Alzheimer’s?

Yes. One of the positive aspects of my mother’s longterm, living under—I hate to talkabout it at all. It’s very upsetting to me. But one plus—one plus—was that she was far more impulsive. She just got things out. She would just say whatever she felt. She’d never been like that. She was very reserved in terms of how she felt. She was very giving and open when she was listening to you, or you were communicating with her. But as far as what she was going through, she never let it out. So I think this was one of the reasons why she had a harder time, but when the disease kicked in, she became absolutely free—free from worry about our response to her responses, to her impulsivity, to what she felt. If she was angry, she was angry. If she was upset, she would cry. If she was happy, she would laugh. That part of it freed her up, and that was wonderful for her, I think, because it must’ve been so difficult to keep all that inside for so long.

I’ll bet your brothers and sisters felt that, too, that they were sort of getting to know her better.

They did. We got a kick out of her. Much of it was really funny. But, of course, not enough. Not really at all. They get very anxious.

While writing your book, you read through your mom’s writings, and you really did get a chance to see a before-and-after difference after the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s.

Not so soon after the diagnosis, but very gradually, just like life, like so much of life, change is very gradual. It did begin to invade her writing. I did write about that, how it went from paragraphs to sentences to words to numbers, and then cute little pictures of kitties with balls of yarn. And those were the last of her collages. She loved cats—she was a cat person. In the last years she lived in Corona del Mar—she was there for 25 years. In the beginning at Corona del Mar, there were these wild cats all over that no one could tame. She would go down and feed them. So she had her cats with her to the very end, two cats—Pablo and J.C.

When you look back on some of your own journals, what were your thoughts about some of the things you had written in the past?

My thoughts were, “I’m ripping this up right now. This is the worst.” And I would. Before I did the book, I had just ripped out pages and thrown them away. They were horrible! Self-indulgent … Horrible! But of course now I wish I hadn’t ripped them all up, because maybe there would’ve been a gem or something I could’ve worked on. I mean, I hated myself. They were just rambling on and on and on. Of course, Mom was guilty of that, too. Because a journal is a journal—the form is not an editorial form. You’re not thinking about what you’re trying to say, you’re just feeling things and putting them down on paper. And believe me, it’s not a fun read. Not with me, it wasn’t. I tore them up. I would save certain things—like mother, I liked a lot of quotes. I liked to see things about anonymous people, or I’d cut things out of the newspaper about my biggest fear, flying. This is of course indicative of, since I’m so afraid to fly, why would I spend my time making my fear ten times worse? It was ridiculous, and at the same time, I was obsessed. There again, like my Mom: saving pieces of paper that meant something to me, writing it down, keeping it …

When your father, Jack, passed …

Can you imagine? The brain went awry with the cancer, and it was right in the frontal lobe. It affected his personality, it affected what he saw. Like, I’d come in, and he’d say, “What are you doing with a gorilla on your shoulder?” Both of them were having their problems with their perceptions of the world, and mother’s inability to remember that father’s becoming just another human being in front of your eyes for five months and then dying of a brain tumor … It’s a lot.

Would you want to talk directly to caregivers? Would you want to give them any advice on how to deal with all this?

I don’t feel like advice is what people need. They need to be heard. And they need affection. Put some animals next to them. That’s one thing I do know. That really did help my mother. It’s soothing. It’s calming. Unconditional love—you have a cat around, and they jump on your bed and you pet them. Or a dog … For lots of people, not just people who are suffering.

My mother was taken care of in her home. She died in her home. Lucky … Lucky that there was money, and that’s not right.

I only know the experience of it. You shut your mouth and listen, and just be supportive. There is no “no” … No no no. That’s out! It’s to make them feel better.

I remember when my dad was sick with cancer. My mother was so devastated and so upset, and wanted to do the right thing that the doctors told her to do for Jack. And they put dad on an experimental program, and of course he flunked it! And they kept telling her, “Make him eat, make him eat.” Well this became the brunt of so many arguments, so much trouble. He was dead in five months. What for? It doesn’t make any sense at all. If the guy’s not going to eat, he’s not going to eat. He’s going to die, so let’s make this time amicable, as best we can, affectionate. Because you’re supposed to do the right thing, you are making that time you have together conflicted, unpleasant. It’s unpleasant anyway. I think that’s all you can do, to make them comfortable. Bring the dogs and cats in. Whatever they want. Who cares.

A lot of people will wonder about the title. Did you want to comment on that?

I think I answered that question in the end of the book. That’s what it felt like. It felt like I was there again, that I was back there with my mother by reading it and by experiencing what I felt. It put me there. That’s why I called it Then Again. The fact that she left this document, these volumes, made all the difference because it gave me an opportunity to take another look at my life, to feel things that I felt that I couldn’t really explain to myself or tell myself I was feeling when I was with her, to know how much I loved her. To remember the times, like getting in the car and collecting junk from the trash cans of department stores. That’s what it was like, it was like I was there again with her. And it was bittersweet, but it was something that I needed to do, so I could really know what, and why, this person that gave me life, was in fact the most important and most influential person in my life. And I feel like mothers don’t get credit. They should be paid for their services, believe you me, I believe that. But paid in the way of taking the time to let them be people, not our mothers, and what we want from them, or why we’re angry with them, the history we have with them. There are certain things that are so annoying about them. But just let that go. Let the moment happen when you’re not carrying around your baggage and you can just look at them and be so grateful to them and love them. They deserve it! ■

Then Again is available in hardcover, paperback, and ebook wherever books are sold.