Days after an 88-year-old resident of an Eastern Oklahoma residential facility went missing, he was found in Flagstaff, Arizona. A 71-year old Texan who wandered from his home was located the next day, disoriented but alive. A North Carolina 20-year-old was found safe the day after getting lost during a bike ride. All suffer from cognitive impairment, and all were located after Silver Alerts were issued on their behalf.

Silver Alerts notify the public via roadside signs, radio announcements and other media that a memory-impaired person is missing. Although they are most commonly associated with missing seniors, they are sometimes also activated to help locate adults who suffer from other forms of cognitive impairment (such as developmental disabilities). Silver Alerts are modeled after Amber Alerts, which are put in place to find missing children

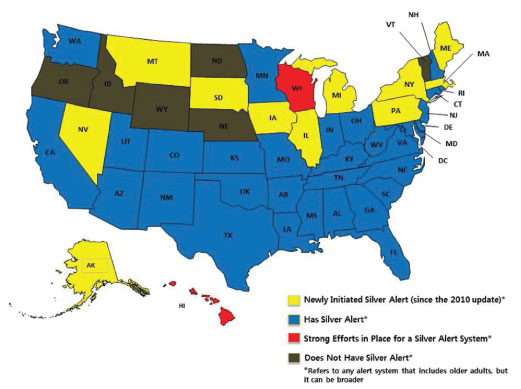

Since Preserving Your Memory first reported on this topic (see “Silver Alert Finding Its Way Home” in our Spring 2009 issue), awareness has spread across the country.

Federal Silver Alert legislation was initially introduced to the U.S. Congress in 2008. A bill passed in the House of Representatives in September of that year, but the 110th Congress adjourned before the Senate could consider the issue. A revamped program, known as the National Silver Alert Act, was re-introduced to the House in February 2009, but was not taken up by the Senate. The policy’s most recent iteration, the National Silver Alert Act of 2011 (referred to as S. 1263) was introduced in June 2011, but was referred to committee, where it remains. As such, there is currently no official Silver Alert program backed by federal funds. However, awareness has grown and an increasing number of state and local governments are implementing Silver Alert-style programs of their own.

In the first half of 2013, Silver Alerts are credited with helping locate 80 missing seniors.

According to Martha Roherty, executive director of the National Association of States United for Aging and Disabilities (NASUAD), localized programs can actually enhance the effectiveness of these safety-based initiatives while also providing an important educational component for first responders. “The beauty of Silver Alert programs is that they bring together state and local agencies that haven’t traditionally worked together. It gives law enforcement an opportunity to partner with social services to ensure the safety of citizens, helping them stay in their homes and their communities longer,” says Roherty. “Lots of training has taken place in recent years to teach law enforcement officers how to work with individuals with memory impairment and other cognitive disabilities so that these agencies and their officers can become more sensitive to the needs of various groups of citizens. Part of that has come about directly because of programs like Silver Alert,” she adds.

According to NASUAD, 42 states plus the District of Columbia and New York City have now instituted official Silver Alert programs, and two additional states have begun legislative efforts but have yet to implement programs. While each state and municipality tailors its program to suit the specific needs of its citizens, all share the goal of protecting vulnerable adults.

“Some of the states have been slower to adopt Silver Alert programs for various reasons,” reports Roherty. “Some are reluctant to do it because of privacy concerns, and many say the cost of implementation is just too high.” In addition, she explains, some law enforcement agencies resist Silver Alert programs because of concerns that they will be used as a crutch. “Quite frankly, some police departments are nervous that if there are community alert systems in place, assisted living facilities and family members might rely too heavily on them instead of adequately caring for individuals with cognitive issues,” she says.

Still, one need only look at the proven results of Silver Alert initiatives that are in place. In Florida, where more than four million citizens are aged 60 or older and more than half a million of those seniors are said to have some form of memory loss, the success stories pour in. In June 2013 alone, 14 missing seniors were found and returned to safety, thanks to Silver Alerts. In the first half of 2013, Silver Alerts are credited with helping locate 80 missing seniors.

Mary M. Barnes, chair of Florida’s Silver Alert Support Committee, summarizes the importance of her state’s efforts this way: “Individuals with dementia are at the greatest risk for wandering, and they make judgmental errors such as driving into wooded areas or water, driving the wrong way on the road and not recognizing road signs. The Silver Alert is vital to protecting a very fragile and vulnerable population in Florida, and it may help prevent a tragedy.”

42 states plus the District of Columbia and New York City have now instituted official Silver Alert programs.

Even without the backing of federal legislation and even when they’re called by other names, Silver Alertstyle communication strategies are helping to return cognitively impaired adults to safety in communities throughout the country. In the words of NASUAD’s Roherty, “As the aging population continues to grow, the need for these wrap-around resources will become more of a priority for states. Silver Alerts are a small but important portion of those types of programs; they can provide comfort to caregivers and family members who will know that in an emergency, there are tools that can be used—and have been used effectively—to help bring people home safely.”