August 11, 2015

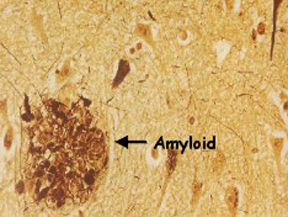

Beta-amyloid, a toxic protein when it builds up in the brain to form plaques, is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. But many people have beta-amyloid buildup in the brain for years without showing severe memory loss or other symptoms of dementia.

Now, two new studies, the largest and most detailed to examine the role of beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s to date, took a closer look at beta-amyloid buildup in the brain. The findings, published in JAMA, a journal of the American Medical Association, could have important implications for diagnosing Alzheimer’s at an early stage, when treatment might be most effective. Better understanding of how beta-amyloid affects the brain could also lead to new approaches to prevent the disease, which affects some 25 million people worldwide.

In one study, researchers from Maastricht University in the Netherlands pooled data from 55 studies to examine more closely the buildup of beta-amyloid in the brain. Altogether, they looked at medical records from more than 7,500 men and women who ranged in age from 18 to 100.

Some of those in the study had memory complaints; others did not. There were 2,914 men and women who were free of memory problems; 697 had subjective complaints of memory loss; and 3,972 had been given a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, or MCI, a form of memory or other cognitive loss that can precede Alzheimer’s disease.

Overall, the researchers found that beta-amyloid brain plaques tended to increase with age. Among those with normal memory and thinking skills, about 10 percent showed abnormal beta-amyloid levels at age 50; that number increased to about 44 percent by age 90.

Beta-amyloid levels tended to be slightly higher among those with so-called subjective memory problems. People with subjective memory problems feel like they are having memory problems, while others — family, friends, coworkers — do not notice that the individual has a problem. About 12 percent of those with subjective memory problems had signs of beta-amyloid buildup at age 50; that number rose to 43 percent by age 90.

Among those with mild cognitive impairment, about 27 percent had signs of beta-amyloid buildup by age 50, rising to 71 percent by age 90. The 20 to 30 percent higher prevalence of beta-amyloid buildup in those with MCI is consistent with its being a risk factor for full-blown Alzheimer’s. Not everyone diagnosed with MCI had evidence of beta-amyloid buildup, however; some of these people may have had depression or other brain disorders, the authors speculate.

Carrying the APOE-E4 gene, which increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s, was associated with higher beta-amyloid levels over all. Among those without memory loss or other symptoms of Alzheimer’s, more than 80 percent of those with the APOE-E4 gene had evidence of beta-amyloid plaques. Only 40 percent of those with normal memories who did not carry the gene had evidence of beta-amyloid buildup.

Being well educated also seemed to protect against Alzheimer’s. In the study, those who were highly educated tended to show fewer signs of memory or thinking problems than those with less education, despite having similar or higher levels of beta-amyloid buildup. They also tended to show signs of Alzheimer’s at a later age. The findings are consistent with the so-called cognitive reserve theory, which posits that education builds up a rich network of brain cells and connections that compensate for the loss of brain cells that occurs with Alzheimer’s.

The researchers concluded that risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease, including symptoms of memory loss, advancing age and the APOE-E4 gene, tracked closely with rising beta-amyloid levels. They also noted that beta-amyloid buildup may begin 20 to 30 years before full-blown Alzheimer’s develops. The results, they say, imply “that there is a large window of opportunity to start preventive treatments.”

But many people with high beta-amyloid levels showed normal memory and thinking skills. “Not all persons with amyloid pathology will become demented during their lifetime,” they note, “and not all individuals with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s-disease-type dementia have amyloid pathology.” High levels of beta-amyloid “should not be equated with impending clinical dementia but rather be seen as a risk state.”

In the second study, researchers at the VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam pooled data from studies that used PET brain scans to assess levels of beta-amyloid buildup in the brain. They gathered records from 1,359 men and women who were living with Alzheimer’s disease and 538 adults with other forms of dementia, and compared to 1,849 healthy controls without memory problems and 1,369 people with Alzheimer’s who had died and whose diagnosis of Alzheimer’s was confirmed by biopsy.

They found that among those with Alzheimer’s, about 88 percent over all had signs of beta-amyloid buildup on PET scans. But curiously, that number decreased with age, dropping from 93 percent at age 50 to 79 percent at age 90.

Carrying the APOE-E4 gene led to more consistently high levels of beta-amyloid. Among APOE-E4 carriers, the prevalence of beta-amyloid remained above 90 percent, regardless of age. In contrast, among those who did not have the gene, the prevalence declined from 86 percent at age 50 to 68 percent at age 90.

Different patterns were observed for those who had forms of dementia other than Alzheimer’s. In these people, beta-amyloid levels tended to increase with age, and were higher among APOE-E4 carriers.

The authors conclude that PET scans may be most useful for diagnosing Alzheimer’s at its earliest stages. They also note that “amyloid imaging might have the potential to be used to rule out Alzheimer’s dementia regardless of age.”

By using diagnostic tests to look for signs of Alzheimer’s damage in the brain, even decades before symptoms begin, researchers are moving closer to one day developing effective treatments for the disease. Targeting people at risk may also allow for one day preventing the onset of full-blown Alzheimer’s in those most likely to develop the disease.

By ALZinfo.org, The Alzheimer’s Information Site, reviewed by William J. Netzer, Ph.D., Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Research Foundation at The Rockefeller University.

Sources:

Willemijn J. Jansen MSc, Rik Ossenkoppele PhD, Dirk L. Knol PhD, et al: “Prevalence of Cerebral Amyloid Pathology in Persons Without Dementia.” JAMA May 19, 2015;

Rik Ossenkoppele PhD, Willemijn J. Jansen MSc, Gil D. Rabinovici MD, et al: “Prevalence of Amyloid PET Positivity in Dementia Syndromes.” JAMA May 19, 2015;

Roger N. Rosenberg MD: “Defining Amyloid Pathology in Persons With and Without Dementia Syndromes.” JAMA May 19, 2015.